‘Do not go to the place where the Dead walk’: Birth, Burial and the Maternal in Pet Sematary

February 9, 2021 ● Catherine Jablonski

Horror is maternal, constantly exploring the struggle between the earthly natural realm where women are placed with flesh and blood, against the sterile masculine world. Mary Lambert’s Pet Sematary, which is to date the highest-grossing horror film by a woman, follows a doctor and his family with the ability to reanimate the dead and shows the consequences of wielding this maternal power. The horror of the 80s relied upon the gender binary - men are punished for creating life outside of the womb, and the women are punished for procreating without men.

Many horror films follow the narrative of a scientist or a doctor who comes up against regenerating nature and the abject, which can mutate the human body through a sort of birth. A good example of this is Seth Brundle (Jeff Goldblum) in The Fly, a scientist who tries to teleport himself, mutating his DNA into a half-human and half insect creature, who then is born out of a metal womb. The flip side of this is shown in The Brood, again by Cronenberg, the mother (Samantha Eggar) creates mutant babies through her emotions, who then grow on sacks on the exterior of her body.

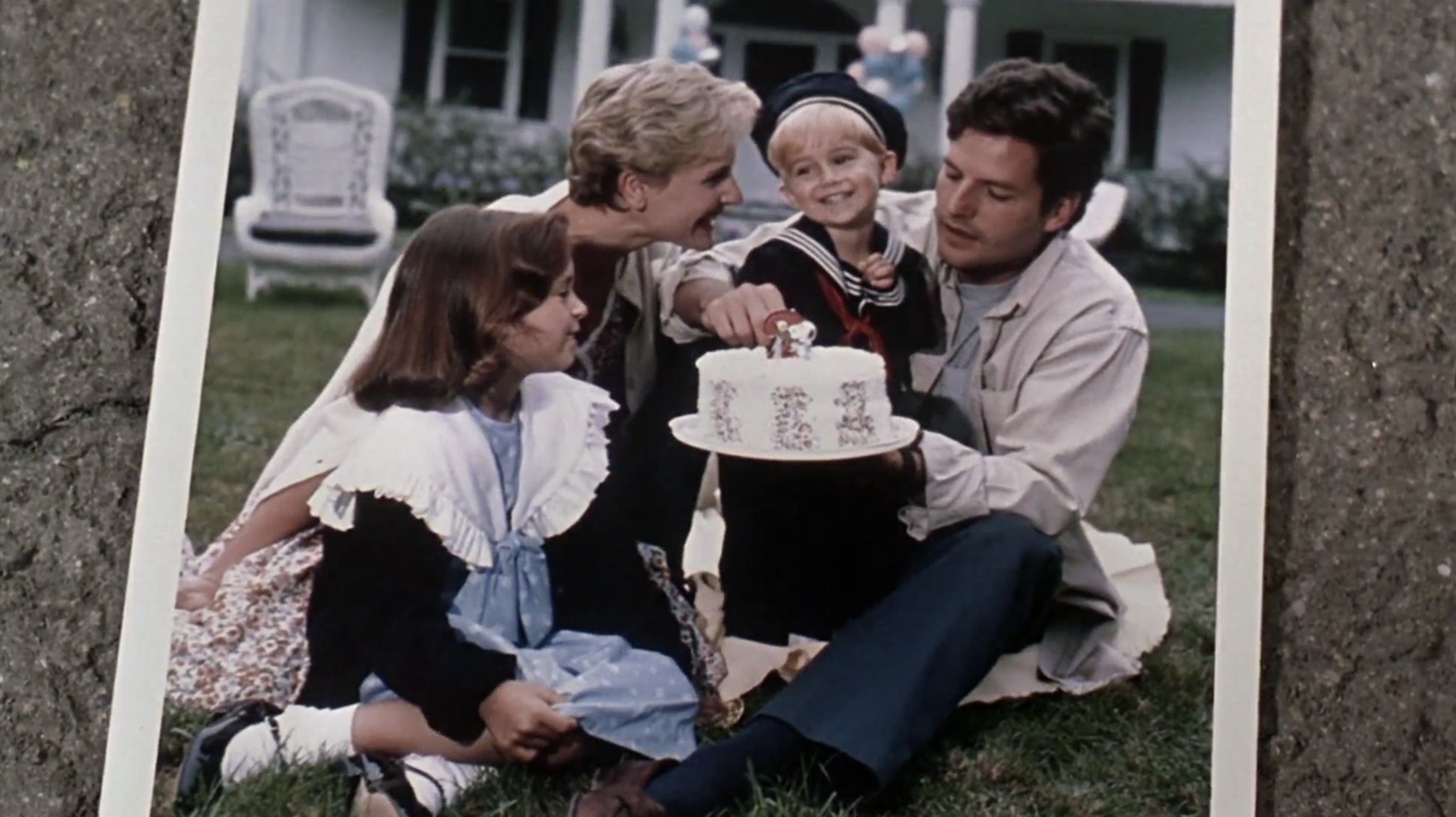

Pet Sematary explores a ‘perfect’ family, moving into a house next to a highway with a constant line of oil trucks driving up and down. The father Louis (Dale Midkiff) relocates the family to the house after getting a job as a physician at the University of Maine, and the mother Rachel (Denise Crosby) stays at home with their two young kids Gage (Miko Hughes) and Ellie (Blaze Berdahl). Down a path behind their house, there is a cemetery where the children’s pets who are killed on the road get buried, but beyond the cemetery, there is a soil where anything that is buried within it will be reincarnated. The soil is the all-consuming womb, the ground takes them in and spits them out, mutated and transformed, like the undead busting out of their graves in zombie films. These creatures reside in a place of in-between, the soil creates doubles of those who are buried, murderous, soulless and smelling of the grave.

Church the cat is brought back to life to spare the daughters feelings of grief but is now violent, strange and with glowing eyes. Later the taboo of human burial is brought up as Gage is killed by a truck, and the father buries him in the soil of the place beyond the cemetery. Gage is reborn, with a new lust for murder, killing Jud (Fred Gwynne) and his mother with his father’s scalpel. The soil was once a Native American burial ground, now unused because the ground became sour, anything resurrected in it becomes evil. The father controlling fate the first time with Church, released the ‘sourness’ from the dirt into the world of the living, changing the fate of Gage and leading to his death on the road.

The father is a doctor, controlling life and death as a day job, placing him directly with the sterile and scientific place in the narrative, in binary against the mother who is positioned with death and decay with flashbacks of her caring for her sister Zelda (Andrew Hubatsek), who is hidden in the backroom and dying from spinal meningitis, causing Rachel to be haunted by witnessing her death. The father tries to command and upset this natural order, creating life outside of female birth. Whatever comes from the soil is liminal, and free from boundaries, as Jud says ‘whatever lives in the ground beyond the Pet Sematary ain't human at all.’ The perfect family unit we see in the opening of the film has now been destroyed, with the young son killing the mother. The father is punished for trying to control the maternal power of life, and his family is dead because of it, the barrier of life and death was never meant to be crossed.

Pet Sematary is a product of the 80s. It showed the changing role that men had in the family as mothers worked more than the decades previous, meaning fathers were more involved in home life. Horror of the times reflects the changing gender roles and warns us of crossing the gender binary. Pet Sematary and horror of the 80s came out around the era of feminism when the importance was placed on the female body and anatomy. For a modern audience, gender is much more fluid, films that explore the feminine and masculine binary seem very outdated, relying on societies views and fear of the breakdown of gender, which cannot create horror for today’s audiences.

Pet Sematary acts as a warning of the masculine characters trying to control the maternal power and a parable against playing God. Pet Sematary examines the universal fear of death, a sort of modern retelling of the monkey's claw story with soil that can bring back the dead, the main takeaway of the film is ‘sometimes dead is better.’

Catherine Jablonski ● Writer

Twitter: @k1tchen_sink_

Instagram: @catherine_jablonski_

Photographer and occasional filmmaker, I spend my time watching Horror B movies and dreaming of living in a haunted house.