Hostel: Part II and Elizabeth Bathory: A Sexual Awakening

A personal and political discussion of the female sadist within the ‘torture porn’ genre and the importance of the Elizabeth Bathory-inspired scene in Hostel: Part II (Dir. Eli Roth, 2007).

April 16, 2021 ● Katherine Armstrong

Screen Gems

My introduction to the ‘torture porn’ genre began on family trips to Blockbuster. Even though we avoided it, I’d be able to catch a glimpse of the black, grey and red covers of the ‘horror’ aisle. Eventually, on these family trips, I would wander the shop on my own and find myself walking briskly past these DVDs, my eyes darting from Saw (2004) to Hostel (2005) to whatever seemed to be the most disturbing. Each trip seemed to beckon me closer to them. But as close as I got, I never had the courage to pick one up.

I was never a rebellious child or teenager in the typical sense. The thought of disappointing my parents was so ingrained in me it took years to challenge. My ‘rebellion’ came later, with the onset of mental illness. It was a rebellion in hiding: Tumblr relationships with older men, a kitchen knife in my knicker drawer and of course, working my way through lists with titles like ‘Most disturbing films ever’ and ‘Top ten banned films’.

Consequently, my mind was filled, whether I realised it or not, with images of women being tortured by men.

The violence of torture porn always seemed orchestrated or motivated by men. In the U.S.: Saw, Hostel, The Collector (2009), remakes like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003) and The Hills Have Eyes (2006). Graphic depictions of male sadism found their way into the most mainstream likes of Seven (1995) and Hannibal (2001), and in other countries like Japan: Grotesque (2009) and the Guinea Pig series (1985-1989).

I’m bored just thinking about cinema’s saturation of ‘man hurt woman’ films. When women commit sadistic acts it’s usually because they’ve already had some horrific act inflicted on them (I Spit on Your Grave (1978), The Last House on the Left (1972), Hard Candy (2005), Waz (2005)). Even Martyrs (2008), in which the criminal organisation is headed by a woman, has to mask its sadism under the pretence of a pseudo-philosophical desire for knowledge of the afterlife, instead of the pure sadistic desire it probably is.

For me, this apparent avoidance of ‘real’, female-perpetrated sadism in mainstream film was finally addressed in Hostel: Part II (2007) and a particularly bloody scene depicting a tied-up woman, a scythe and a woman known in the credits as Mrs Bathory, obviously inspired by the infamous serial killer, Elizabeth Bathory.

Hostel: Part II, like its predecessor, follows three young people on holiday, lured to Slovakia under false pretences and sold to the ‘Elite Hunting Club’ to be tortured by rich, usually male, clients. But, this time, instead of sex-obsessed fratboys looking for the most beautiful women to fuck, it's women in search of relaxation. In simplistic terms: there’s Whitney (Bijou Phillips), the slut; Lorna (Heather Matarazzo), the virgin; and Beth (Lauren German), the heroic final girl who embodies neither stereotype.

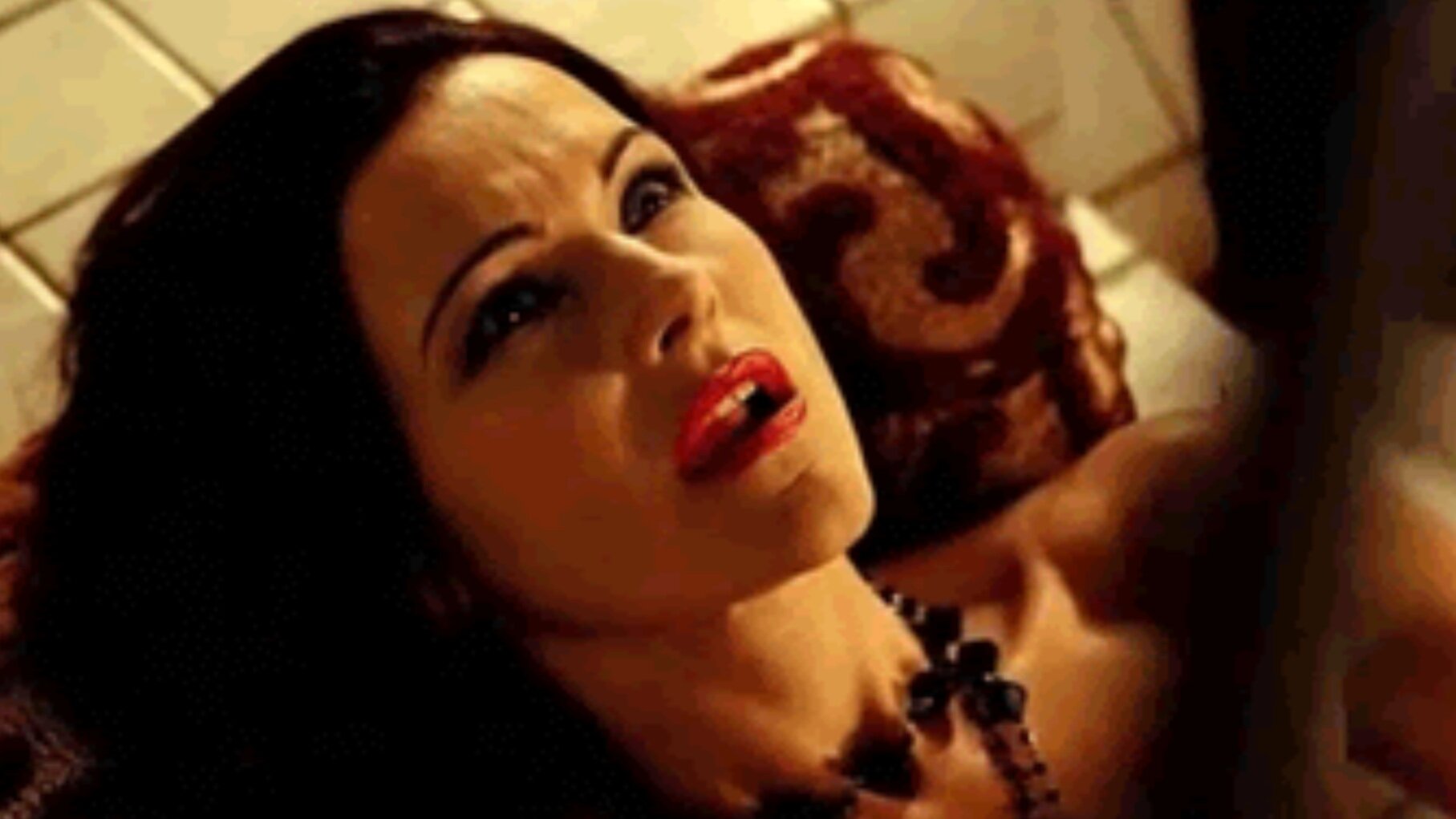

In the scene, Lorna is hanging upside down, gagged, above a sort of large, shallow bath. The room is large and lit only by candles, like a gothic castle. An attractive woman enters wearing a cloak, removes it to reveal her naked body and lies in the bath, underneath Lorna. Then, she picks up a scythe and begins taunting Lorna with its blade, before she removes her gag, listens to Lorna cry and beg, and slashes her with the scythe. She rubs her naked body with Lorna’s blood and finally, slits Lorna’s throat before gasping almost orgasmically.

Monika Malacova as Mrs. Bathory, Screen Gems

Never before had I seen such suffering produced for its perpetrator’s pleasure when that perpetrator is a woman.

However, is the desire, as a woman, to hurt other women, anti-feminist? I think the female gender of the victim, in this case, has its own importance. If the victim was a man would we automatically assume the assailant was motivated by revenge against her oppressor (as in the previously mentioned torture porn films)? Or is there something else going on? Lorna, a victim of her own naivety, perhaps, had been lured to the Elite Hunting Club headquarters by a man she thinks she is in love with. There’s a hint of the Marquis de Sade’s philosophy within her death scene. Here, a woman clearly in touch with her sexuality triumphs over the innocent and prudish Lorna. Like de Sade’s characters, Justine and Juliette, these two extreme representations of embracing or rejecting sexuality present a clear winner and loser. It’s as though Lorna, as a symbol of repressed desire, must be destroyed for Mrs Bathory (Monika Malácová) to realise her own.

I was aware of the 16th Century Hungarian Countess years before I watched this scene. There was a book in my primary school’s library with a very small paragraph about her that I would read over and over again with fascination. Elizabeth Bathory was perhaps just as good an inspiration for the ‘vampire’ as Vlad the Impaler. According to legend, she bathed in the blood of virgin women to maintain her youth, although it’s more accepted by historians that her proclivity for torturing and murdering young women was derived from sadistic pleasure.

The only known portrait of Elizabeth Bathory.

Other depictions of Elizabeth Bathory seem reluctant to present her as sadistic, instead diagnosing her proclivities as reactions against childhood trauma and the delusion that the blood of young women will prevent her from ageing (The Countess, 2009) or lies made up by a rejected admirer accusing her of witchcraft (Bathory, 2008). Immoral Tales (1974) takes a surreal approach, finding beauty in images of young female bodies and the countess bathing in blood.

Hostel: Part II’s scene, however, is unapologetic in its depiction of sadism. Heather Matarazzo’s performance as Lorna is raw and emotional, where plenty of other horror films resort to the cheap thrills of high-pitched, female screams that almost make you wonder if the victims are enjoying it (because all women are masochists, aren’t they?). The typical aural excess of female screams in horror films, argues Linda Williams, present women as having the sole function of embodying pleasure, fear and pain (Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess, 1991).

Heather Matarazzo as Lorna, Screen Gems

However, through the realism of Matarazzo's performance, we are taken out of the usual horror audience role as passive voyeurs of violence and forced to empathise with the character’s suffering. Perhaps, by cutting between Lorna’s pain and Mrs Bathory’s pleasure we become aware of our own pleasure derived from viewing violent images. Like crowds surrounding the chopping block in the market square, we fill cinemas to watch these violent films. Is humanity’s enjoyment of others’ suffering innate? Wilhelm Stekel, a pioneer of psychological theories of sadomasochism, said, “In the human soul, cruelty crouches like a beast, chained, but eager to spring.” Maybe there is something of a sadist in all of us.

Additionally, I would also argue that Mrs Bathory’s obvious sex appeal and nudity is not entirely for the benefit of the male gaze, but to make us hyper-aware of her ‘femaleness’ and make it inescapable for us to see a woman as a sadistic torturer.

In Hostel: Part II, I finally saw a female character who inflicts pain for her own pleasure, and hers alone.

‘Pleasure’. This word made me uncomfortable for many years in the same way words like ‘moist’ and ‘slough’ do to many people. It gave me a faint discomfort akin to hearing nails on a chalkboard. There are many women, including me, who often don’t feel like they deserve pleasure, and they certainly don’t demand it. And if we think we don’t deserve pleasure, do we become accepting of pain?

Childbirth is painful. Losing our virginity can be painful. Penetration is more likely to be painful for the woman than the man. Men’s natural strength, if they use it, allows them to inflict more pain. Our bodies cause many of us throbbing pain in the form of menstrual cramps and we bleed - we literally bleed - once a month for decades. Since our conception, our bodies seem designed to ache, apologise and acquiesce. Helene Deutsch said that masochism in women ‘represented a biological mechanism of human adaptation of the female to the painful experiences of menstruation and childbirth” (Psychology of Women, 1944).

Expressions of non-sexual masochism are common in women attempting to cope with mental pain. Some of us use pain, not outwardly or spontaneously with outbursts of anger (e.g. punching a wall), but inwardly; measured and calculated. Think of the thousands of young women with arms covered in raised scars; women who devise methods of self-harm like the unscrewing of pencil sharpener blades, forced vomiting with toothbrushes and secret starvation.

Is this calculated and aesthetic approach to self-harm representative of the ‘feminine’, and is this indicated in Mrs Bathory’s scene in Hostel Part: II, with the elaborate, symmetrical set, paid for by the client?

In the past, my own anger always turned inwards. I was taught to be restrained; emotional and sensitive, but never angry towards anyone but myself. I wonder if any desire I have to inflict pain on others is a direct reaction to the pain I’ve inflicted on myself over and over again.

Is being sadistic, as opposed to masochistic, the complete antithesis of what it means to be a woman?

More specifically, as Anna Katharina Schaffer states in her examination of sadistic women in literature: “The sadistic woman violates both latent and overt gender stereotypes in the most radical manner.” (Visions of Sadistic Women: Sade, Sacher-Masoch, Kafka, 2012). Is Hostel: Part II’s Mrs Bathory an image of radical, female liberation?

After all that, it’s only a three-minute scene. It’s not a ninety-minute character study. We don’t see into the mind of a sadist like the male protagonists in A Clockwork Orange (1971) or American Psycho (2000). We don’t even know her name.

But, I hope I’ve convinced you of its importance, at least within the torture porn genre. Maybe this was my first time seeing a woman’s dark side in all its bloody glory. Maybe it was because I was tired of watching men have all the fun. Maybe it awoke a desire in me I didn’t know I had.

Now, here I am, probably a decade later, obsessed with sex and torture. Thank you, Eli Roth - even if your only intention was to make a cool death scene. Not all women are masochistic and some of us are even sadistic. Who’d have thought it?

Katherine Armstrong ● Writer

Instagram: @snailsonmyface

Website: www.katherinelouisearmstrong.co.uk

I’m a writer (and aspiring provocateur) from North East England. My work is often extremely personal and I’m particularly interested in exploring realism, British, working class settings, transgression, taboo, sexuality and family life.

I’m directing my first short film this year, ‘I Am Not a Dominatrix’ (IG: @iamnotadominatrix), about a young woman who threatens her relationship when she reveals the extent of her sexually sadistic desires.