The Further Reaches of Experience, The True Horror of Hellraiser

April 13, 2021 ● Kiarash Golshani

“Everything Is About Sex Except Sex. Sex Is About Power.”

Hellraiser is the horror franchise that scares me the most.

What makes A Nightmare on Elm Street horror?

“That’s easy!” you might say, “Freddy’s burnt appearance, sharp claws, and dominion over a realm where you are most vulnerable.”

Saw?

“The creative methods of murder, unpredictability, and Jigsaw’s creepy persona” (which was subsequently destroyed by the later films).

Now, what makes Hellraiser horror?

There is the assumption of the classic “meat-hooks, bodily mutilations, and the shoddily-acupunctured poster character” that will forever be associated with it. While these are staples of the franchise, anyone who has seen it knows that there is something different about Hellraiser. You leave it with a dirty feeling like you have seen something that you shouldn’t have. Consciously or unconsciously, your body didn’t just flinch, your brain flinched. You start to think about it more and more. The thought festers in your mind like rotting meat. Then you realise just how absolutely insanely horrifying the thing you just witnessed was. I’m about to highlight what I find makes Hellraiser a battering ram to the senses, and just how brilliantly it managed to execute its concepts with its subversive charm. An Orphean descent into Barker’s hell. Oh, and this contains heavy spoilers for the first film. You have been warned.

Shall we begin?

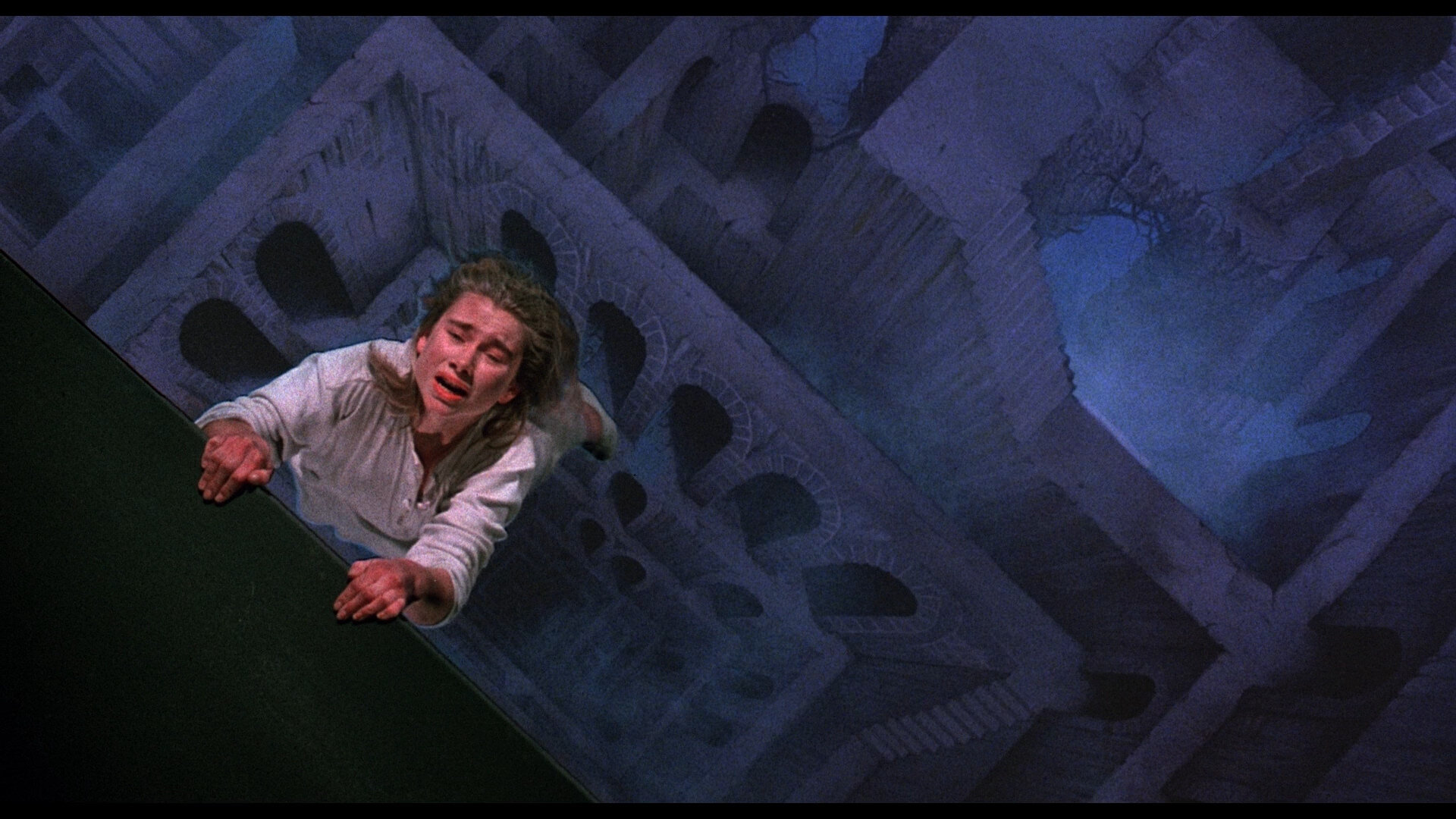

Hellbound: Hellraiser II (1988), New World Pictures

In an age of slashers, Hellraiser (1987) arrived to rearrange the formula. But before all of that, dread maestro Clive Barker sat slouched over his typewriter composing The Hellbound Heart.

Britain in the 80s was nearing the end of the sexual revolution. By 1986, all that was left of free love was slowly being lowered into a casket. During a time where young people should be experimenting the most, a callous disease crept into their lives and began killing the unsuspecting people. The AIDS epidemic, and the paranoia that came with it, had brought it to a screeching halt in an event so devastating that we still feel the reverberations today. During that time, sex and horror were tightly linked.

Clive Barker was a sex worker at the time who sought to channel the resentment brought about by the end of the sexual revolution through his novella. The book also portrays the existential nightmare that is industrial Britain as it concerns a family moving into a crappy property in a coal town. Beneath this premise lies something far more sinister, with demons and hedonist rapists fireballing into their lives (I have skipped over an absolute truckload of extra information on the premise, but if you haven’t already seen Hellraiser, then you’re doing yourself a disservice).

Hardly any of the major plot details were changed for the film, which was a rare case as the writer of the source material was given free rein to write/direct his own adaptation. From this, we are given Hellraiser (1987). The movie, now in a vaguely American setting, only has a few discrepancies with the novel, such as less detail for the torture and a changing of Pinhead’s sex from female to male. Yet the unsettling mechanical atmosphere from the source has remained gloriously untampered.

Looking at the film with a modern gaze, the special effects – while impressive – unfortunately, do not hold up very well. For the time though, they were the height of grotesque. The film was teased with a rare X rating for its explicit violence and depiction of sex, which Barker gives a Brando-esque anecdote: “The MPAA told me I was allowed two consecutive buttock thrusts from Frank, but three is deemed obscene!” While scenes of mutilation were also deemed “too far”, the film truly proved the disconnect that American censors had between sex and violence, with sexual scenes being perceived as far obscener than their violent counterparts.

But therein lies the crux: sex is the disembodied and beating heart of Hellraiser’s modus operandi. This clearly scared the Puritan censors enough that they felt it less appropriate than a man getting ripped to shreds with hooks. Says a lot really.

The sexual horror of the first film is perfectly embodied by the antagonist, Frank Cotton (Sean Chapman). He is an amalgamation of everything horrifying about the sexual nature of humans and the depths of depravity our brains are capable of. From the get-go, he is implied to have exhausted the sexual experiences of the world enough to use the Cenobites’ summoning box – the Lament Configuration, including the most depraved ones. He is depicted as a foul, sleazy, abusive, and overall horrific figure that hangs over the rest of the cast like a dark cloud. Among other famous real-world deviants such as Marquis De Sade and Gilles De Rais, Frank’s actions are not rooted in fantasy, but the cruel reality in which we live. This unfortunate truth only serves to make him that much more terrifying.

He solves the puzzle box before the Cenobites - the Order of the Gash – arrive then drag him down to their realm to experience torture beyond the reaches of pleasure and pain. The Cenobites themselves were designed after Barker’s time perusing through BDSM clubs and their patrons, seeing how their libidos were tied to leather and piercings. Led by the iconic Pinhead, they appear to be above the human perceptions of the senses. Compared to the contemporary slashers the Cenobites appear more bureaucratic in their manner. They are not without contemplation and are open to bargaining with their prey. Their only concern is how long they can torment their victims to feel every last bit of emotion drain into their own stygian arousal for a time too long for our brains to fully comprehend. Sex taken to its logical extreme. Not only that, but their presence in the films is electric, there’s palpable tension before they arrive in their grandiose light show with the tolling of their ghostly bell. They remain among the most unique icons of the horror rogue’s gallery.

This is what separates Hellraiser from the rest of the horror stock. Barker was not afraid to touch upon real-world taboos to create a unique experience. Horror works best when it is tackling the intangible. The aforementioned Elm Street’s focus lies in the liminal world of dreams, Final Destination relies on the primeval fear of imminent death to get under the skin of its viewers, and Alien on the horrors of space. Hellraiser’s forte lies in its pairing of sex and violence to create its uniquely uncomfortable watching experience. It highlights the brain’s endless potential for brutality in all its forms, and monstrous men act as its enabler. These sadistic characters permeate the story as the memorably cruel antagonists.

Who better to take down these threats than the franchise’s women?

Kirsty and Tiffany, Hellbound: Hellraiser II (1988), New World Pictures

With its themes of male violence, the female gaze is prevalent throughout the franchise. Kirsty Cotton (Ashley Laurence) stands on her own as truly the first and final girl, she never goes down easy, always physically fighting against otherworldly forces. She stares the angels of pain directly in the face, lets out a defiant “Go to Hell!” in a triumphant moment. An absolute boss throughout the films that she appears in, Frank and the Cenobites are viciously warred against by her strength of will.

On the other side, Julia Cotton (Clare Higgins) – Kirsty’s evil stepmother (in the goriest sense possible). A deconstruction of the trope, Julia Cotton is the secondary turned primary antagonist of the first two films. While she initially works with Frank as an accomplice for his schemes, she is not completely treated without sympathy as a villain. During the first film, she is shown as being slowly corrupted by Frank’s influence, begrudgingly bringing bodies for him to regenerate from – which she eventually embraces. While her end in Hellraiser is a result of Frank pitilessly turning his back on her, her return in Hellbound (1988) leaves her untethered from her abuser and free to seek her own way back into the mortal coil through similar means.

They are two sides of the same coin. Yin and Yang. Two women subjected to torment in different ways. Their destinies are entwined, but their fates are distinct. If audiences did not take to Pinhead so strongly in the first two films, then Barker says that Julia would have been the series antagonist. It would have been nice to see a female villain with her own aspirations after breaking free from her male influence be an overarching threat.

Since I really couldn’t do this section without mentioning her, appreciation should also go to Joey (Terry Farrell) from Hell on Earth as well. The POV character for most of the film, she goes up against Pinhead himself. Trying to get to grips with her father’s death in Vietnam she enters into the nightmarish Hellraiser world, becoming embroiled in the machinations of the Cenobites. A highlight is when she is being chased by the forces of hell through the empty city streets while being psychologically tortured seeing her friends turned into monstrous beings. Unfortunately, this theme of strong female characters did not continue very far beyond the theatrical films, but in my mind, this franchise will always be associated with having some of the most kick-ass horror protagonists ever to grace the silver screen, even though this fact is sadly overlooked by many contemporary filmgoers.

Joey, Hellraiser III: Hell on Earth (1992), Miramax

So, what is the point of all of this?

The human mind is a powerful thing, and Hellraiser is a crash-course in how to make it writhe. The unknown always makes for better horror, the clever incorporation of the human mind as the ultimate known is the epitome of horror itself. It is a beautiful thing capable of infinite kindness and infinite cruelty – but it is also a deep chasm of vast corridors and caverns (not unlike the realm of the Leviathan) that determines our nature as a species. When asked about how close we are to understanding our brains, Christof Koch, President of the Allen Institute for Brain Science simply replied:

“We don’t even understand the brain of a worm.”

Our most fundamental asset, the thing that keeps us alive and thinking beings, that most powerful of machines that separates us from beasts – and we have yet to even grasp its mysteries. This concept is most brilliantly displayed in a sequence from Hellbound featuring a mental patient who suffers from hallucinations of maggots on his skin. He is given a knife and allowed to tear at his own skin, screaming bloody murder (while we see flashes from 3rd person to his POV) in order to summon Julia back from hell, who proceeds to devour his body. This particular bit is disturbing on so many levels, it activates about five different fight-or-flight reflexes in me.

That is horror, and that is Hellraiser.

My final word on this? I absolutely adore this franchise - and hell, if you were willing to sit down and read my 2000-word explanation as to why maybe you love it too. I hope I’ve shed some light as to why I find this series to be so good in its scare factor. In the immortal words of Pinhead, “It is not hands that call us. It is desire.”

Kiarash Golshani ● Writer

Instagram: @kiarashgolsh

London based hellraiser, kaiju flick and body horror enthusiast - or maybe I'm Barker up the wrong tree.